I talk in my sleep now. I scream, I kick, I cry. When I wake up, I cannot shake the feelings I had in the dream. I used to be able to reassure myself, even in the middle of the dream, that it was only a dream, that I didn't need to be afraid or angry. The dream might even change after that. Now, I wake up certain that my dream feelings reflect reality.

It is 4 AM and I just woke up crying because I was dreaming that my sister and I were fighting, physically like we did as kids. She had me pinned down and was about to do something awful and then she let me go. As my nightmare continued, she walked off like nothing had happened and I demanded to know how she could be so horrible to me, why she didn't love me anymore. The reason, she responded, with finality, was some story about me that our mother had conveyed. It was the disbelief that my sister now longer loved me because of some second-hand information was what led to my tears.

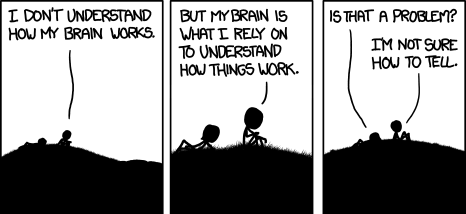

Even as a kid, i had long vivid dreams and could recall the details and the narrative the next day. What a weird dream dream, I would think. Now, even though I wake knowing that the content of the dream is not reality, I feel certain that the underlying feelings are. It is hard to separate "I" from my brain.

Now, as I write this and gradually feel more wakeful, the feelings fade. My husband has been waking me during my nightmares, no doubt in response to being woken, telling me that I am dreaming. He says, wake up and stop having that dream. Easier said than done. It is not really fair to him to have to try and sleep through my tirades, but I am more likely going to stop having the dream if I stay asleep. Dreams pass as we drift passed REM sleep into a deeper more restful state.

What is so upsetting to me is not the dreams but that having a brain injury is so much like that feeling that my perspective seems so real and can be trusted. I was pretty socially savvy before this happened. I made friends easily, was well-liked, but most importantly could breeze through casual social interactions. Put me at a cocktail party and I was perfectly comfortable, engaging with everyone and working the crowd. Now, I am leery and anxious, mostly because I have learned that I might say or do something socially inappropriate. Despite being armed with that knowledge, I am powerless and unaware when it happens. If I am with my daughter, she gently points out that I am arguing with whatever anyone says. My husband scolds me for being childish or inappropriate taking too many desserts or playing with the decor. I recognize when I see the strange blanks stares or when people quickly turn away from me that I must have done something strange.

At my friends Christmas party this year, I was standing at the buffet table. Right nearby three men were chatting when a preadolescent boy tried to dash by. One man stopped and remarked at how tall he had grown. What are you, five three, he asked. The boy nodded and I was struck with disbelief. This kid was clearly at least 4 inches shorter than I am so pointing my finger I interject, exclaiming loudly, "ABSOLUTELY NOT! These is no way he is five three. I am five three so he can't be that tall." Instantly I caught my faux pas as the men quickly averted their eyes. "Sorry. That was inappropriate," I say as I excuse myself retreating to another part of the room.

I laugh when I retell that story because no harm was done and it happens too often for me to be surprised anymore. What preceded my bold statement was the certainty that the men would be grateful for receiving the correct information. Oh, thank you, we needed a benchmark in the form of a five foot three middle-aged woman so we could accurately gauge the boy's recent growth spurt. It is a split second thought process based misreading a social cue that leads to impulsive interactions. The messages that my brain sends me are not to be trusted. My appraisal of the situation and subsequent judgment is incorrect. I know that intellectually but adjusting to not believing my summary of social situations when I used to be so savvy is difficult.

The impulsiveness, the minor arguments, and the slight awkwardness are all tolerable. What leaves me feeling full of despair, hopeless for the future, is my overall assessments of my relationships with the people closest to me. I can be suspicious and paranoid about my family's intentions. I am often certain that my closest friends hate me. When I take the time to spell out, to my cognitive therapist, my husband, or my daughter, each of the clues and messages that led to my assessment, they help me adjust my thinking. I can see how my brain tricked me into reading information incorrectly. I adjust my thinking and feel comfortable again. What is scary is that sometimes I forget that I had that realization. The next day I am mistrustful again. Who will be there to remind me, hey Aly, you figured out that you were reading that wrong and you are cool with it now? If the answer is just me, I am in trouble because my brain is a big fat liar now.